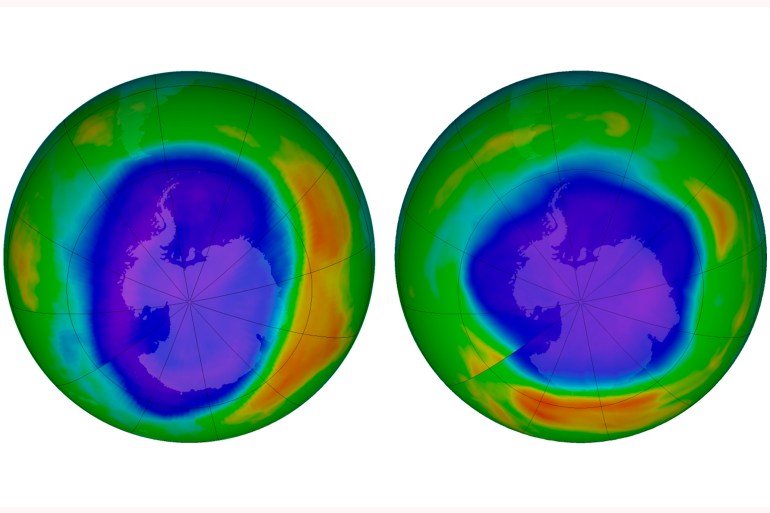

New study says giant hole in the ozone layer that develops every year over Antarctica on course to be healed by 2066.

Earth’s protective ozone layer is healing at a pace that will fully mend the hole over Antarctica in about 43 years, a United Nations report has found.

The scientific assessment conducted every four years found a recovery in progress, more than 35 years after every nation in the world agreed to stop producing chemicals that deplete the ozone layer in the Earth’s atmosphere. The layer shields the planet from harmful radiation linked to skin cancer, cataracts and crop damage.

“In the upper stratosphere and in the ozone hole, we see things getting better,” said Paul Newman, co-chairman of the scientific assessment.

The progress is slow, according to the report presented on Monday at the American Meteorological Society convention in Denver. The global average amount of ozone 30km (18 miles) high in the atmosphere won’t be back to 1980 pre-thinning levels until about 2040, the report said. And it won’t be back to normal in the Arctic until 2045.

The giant hole in the layer that develops every year over Antarctica won’t be fully fixed until 2066, the report said.

Scientists and environmental advocates across the world have long hailed the efforts to heal the ozone hole as one of the biggest ecological victories for humanity. The initiative sprang out of a 1987 agreement called the Montreal Protocol, which banned a class of chemicals often used in refrigerants and aerosols.

“Ozone action sets a precedent for climate action,” World Meteorological Organization Secretary General Petteri Taalas said in a statement. “Our success in phasing out ozone-eating chemicals shows us what can and must be done – as a matter of urgency — to transition away from fossil fuels, reduce greenhouse gases and so limit temperature increase.”

Signs of healing in the ozone layer were reported four years ago but were slight and more preliminary.

“Those numbers of recovery have solidified a lot,” Newman said.

The two chief chemicals that munch away at ozone are in lower levels in the atmosphere, said Newman, chief Earth scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Chlorine levels are down 11.5 percent since they peaked in 1993, and bromine, which is more efficient at eating ozone but is at lower levels in the air, dropped 14.5 percent since its 1999 peak, the report said.

The drop in bromine and chlorine levels “is a real testament to the effectiveness of the Montreal Protocol”, Newman said.

Natural weather patterns in the Antarctic also affect the size of the ozone hole. In the past couple of years, the holes have been a bit bigger because of those patterns but the overall trend is one of healing, Newman said.

A few years ago, emissions of one of the banned chemicals, chlorofluorocarbon-11 (CFC-11), stopped shrinking and were rising. Rogue emissions were spotted in part of China but now have gone back down to where they are expected, Newman said.

A third generation of those chemicals, called HFC, was banned a few years ago not because it would eat away at the ozone layer but because it is a heat-trapping greenhouse gas. The new report says the ban would avoid 0.5 to 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit (0.3 to 0.5 degrees Celsius) of additional warming.

The report also warned that efforts to artificially cool the planet by putting aerosols into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight would thin the ozone layer by as much as 20 percent in Antarctica.