Melbourne, Australia – Saade Melki started using heroin the same week his father passed away. He was 24. Over the next 20 years, the Lebanese-Australian struggled with addiction.

He also struggled with holding down jobs and grew distant from friends and family. He would get clean and had multiple relapses as he tried to kick his addiction.

That life, he now says, “I didn’t want it anymore”.

In early 2020, a chance encounter set his life in a positive direction when he started attending Melbourne’s first-ever Medically Supervised Injecting Room at the North Richmond Community Health Centre – a space where people can use drugs safely, knowing that medical personnel are on hand should something go wrong.

Known locally by its acronym MSIR, it was here that Melki met Margo, his now fiancé, who was also an active heroin user. Margo had lost a partner to a drug overdose. She also witnessed Melki experience his first overdose at MSIR, without whose emergency assistance Melki said he would have died.

“All I remember is waking up with an oxygen mask and feeling a little bit out of it, like ‘Oh what happened?’ And Margo was there. She was crying, saying … ‘You almost died’,” he said.

“Every time I went to [MSIR]there was at least one person with an oxygen mask being saved,” Melki recalls, referring to the lack of oxygen people experience during an overdose.

After that experience, Melki focused on getting clean, taking up long-acting treatment with buprenorphine, which he calls a “miracle drug” and gets monthly for free at MSIR. Injected under the skin, it prevents drug users from going into withdrawal for at least a month.

![A staff member at the reception in the MSIR in Melbourne's North Richmond Community Health Centre - the country's first medically supervised facility for safe drug injection [Sen Nguyen/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/20230417_100934-1-1682670717.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C578)

Eventually, Melki got clean. He has also survived cancer and now, at 49, he works as a scaffolder. It has allowed him to pay for his car and save up to hopefully buy a house and afford IVF treatment as he and Margo plan to have children. Melki has also reconciled with his mother, who he now sees every day, and reconnected with the friends he lost through addiction.

“Everyone’s back, and yeah, I just wanna keep it that way,” he said.

Funded by the Australian government, the supervised injecting room at North Richmond Community Health Centre was established in 2018 to “help stem the tide of heroin-related deaths” in Melbourne, according to a recent review of the facility conducted by the state government.

The review noted there were 20 overdose deaths in Richmond in 2015 alone. Since opening, more than 6,000 overdose events that occurred at the facility were treated and none was fatal. Modelling indicates that about 63 drug deaths have been prevented since the MSIR opened, “which would equate to around 16 lives saved each year”, according to the review.

“It is very clear that this facility has changed lives and saved lives,” Victoria’s Premier Daniel Andrews said last month when announcing the facility would be made permanent after a five-year trial period and rounds of reviews.

“Stories of people dying in laneways and gutters, stories of, literally, dead bodies throughout that local community meant that we needed to do something different, something challenging,” he told local media.

Earlier this month, journalists from Southeast Asia and Australia were invited by the international advocacy group Harm Reduction International (HRI) to visit the MSIR. Proponents say the facility could be a valuable example for Southeast Asia where governments are focused more on punishing drug use than providing facilities that could save lives.

The drug situation in Southeast Asia is significant. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has warned that drug production and consumption is surging regionally. In 2021 alone, more than 1 billion methamphetamine pills were seized by authorities in Southeast and East Asia. Opium poppy cultivation also ramped up last year in Myanmar, with the UNODC expressing concern about the health effects of increased heroin production in the region and beyond.

There are no medically-supervised legal drug consumption rooms in Asia, according to a 2022 report from HRI. Of the 16 countries with such facilities, all were located in the Global North with the exception of one in Mexico.

What is a safe injection room?

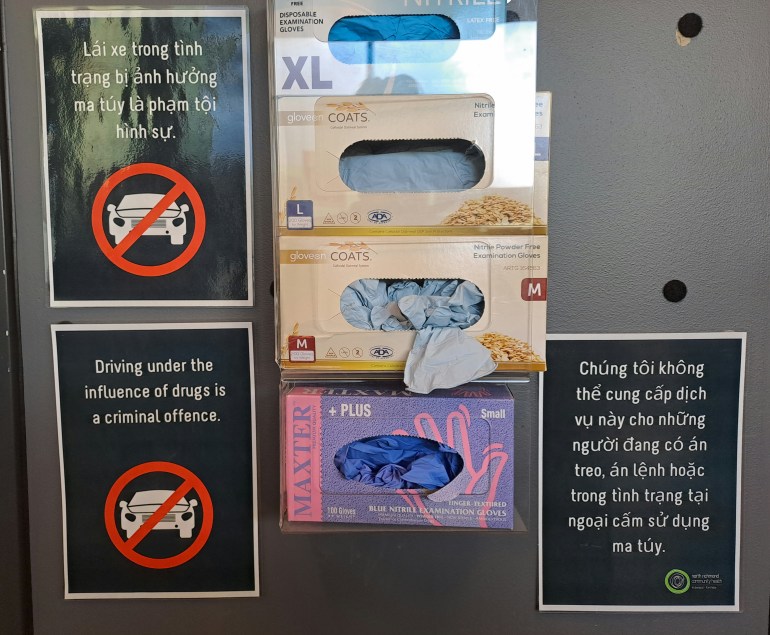

The reception area at MSIR is dotted with motivational art and drug safety warnings in English and Vietnamese. North Richmond has a large Vietnamese community and has earned the title “Little Saigon” due to the abundance of Vietnamese-owned restaurants and businesses.

Drug users are asked at the reception about their health status and the drugs they will use that day before being shown into a staffed injection room with partitioned cubicles where they are given an injection kit that includes a clean needle. They can also ask for medical guidance if they have difficulty finding their veins, which is a common struggle among people who frequently inject drugs.

Those who use MSIR are encouraged to attend a community room and access free addiction counselling and health services, including dental care and tests for hepatitis, a virus that causes liver damage commonly found among people who inject drugs.

Dr Nico Clark, MSIR’s medical director, said the facility has had almost 400,000 visits by some 6,000 users of the service since 2018. Most use heroin and sometimes methamphetamine.

A contextually unique element of MSIR is its location in an area with high rates of drug dealing and public drug use. Just “a few hundred metres away’’ from a street “where people are buying and selling heroin”, Clark said.

“The other thing unique to our service is that we offer a range of health services on-site” that are not available elsewhere in the local community, he added.

Despite its success in saving lives, MSIR is not without its flaws.

While supporters of the MSIR model point to the provision of a safe and supervised environment that protects drug users from harm, critics of the Melbourne facility say that public drug use remains highly visible in the Richmond area and that local residents and businesses feel unsafe owing to loud gatherings near the facility as well as erratic or violent behaviour, according to the recent state-government review.

MSIR also falls short when it comes to other needs, such as mental-health services, which the review described as “a lost opportunity’’.

Public injecting as well as discarded needles and syringes remain a challenge in the area, the review added.

“At its heart, an injecting service is a health response. Its main objective – to save lives – is well accepted in the community. Yet, unlike other evidence-based health policies that prevent death and provide life-changing support, injecting facilities are often highly contested in the public conversation,” the review noted.

Helen Clark, the former prime minister of New Zealand and current chair of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, also visited MSIR in April.

“To think that it’s all paid for by the public is particularly encouraging. And clearly there’s a need for much more in the cities and states across Australia. My own country has nothing like this,” Clark told journalists during the visit.

Southeast Asia’s zero-tolerance drug policies

Southeast Asian countries primarily take a zero-tolerance approach to drug use.

In Vietnam, drug-use responses fall within the legal framework of the country’s HIV prevention efforts, said Nguyen Minh Trang, programme manager of the harm-reduction and addiction-treatment programme at Hanoi-based non-profit Supporting Community Development Initiatives (SCDI).

“But there are still limitations because harm reductions are not only needed in the HIV area but also others, such as overdose,” she said, adding that by law only a licensed doctor can administer medication that reverses opioid overdose.

Vietnam is “more progressive” than many other countries in the region, Nguyen said, as services provide clean needles and syringes to drug users but not a safe space where those needles are then used.

If Vietnam were to consider safe-injecting facilities, Nguyen said, new laws would be required to ensure people would not be arrested or discriminated against.

Although Thailand appears to be more liberal, becoming the first country in Asia to have legalised the sale and consumption in private of cannabis, Nilawan Pitakpanwong, a member of the Thai Drug Users’ Network, also pointed to laws needing to change to protect drug users from harm.

“Our drug users inject themselves at [home]or in the forest, or in the farm [so] that nobody knows they inject. So this is not safe for them,” she said.

“If we have a drug consumption room for them, they can just come in and inject and we have a doctor and a technician-professional to look [after them] and to help reduce overdose.”

Years of prohibitionist drug policies have created a global fear of drugs, said Dr Gideon Lasco, a senior lecturer at the University of the Philippines. Harm reduction has also become politicised as it is seen as a Western imposition in post-colonial societies in the region.

“It’s easy for politicians to say, ‘Oh, but we shouldn’t be doing that because we will not be dictated upon by the West”, the physician and medical anthropologist said.

“If we see this as a kind of journey from this very punitive regime to something that’s more progressive and more effective, then the first step is to try to dismantle this kind of highly criminalised approach that leads to people spending so much time in jails before even getting the trial,” he added.

But the Philippines – where former President Rodrigo Duterte’s “war on drugs” led to thousands of killings of drug users and dealers – is likely “still very far from” accepting supervised injecting facilities, Lasco said.

“Mass incarceration is still out there and the penalties are so harsh.”