Bill was standing with a group of people mostly in their 20s when a young woman started to lead the chanting. “Give me liberty, or give me death,” she shouted, her voice cracking at one point.

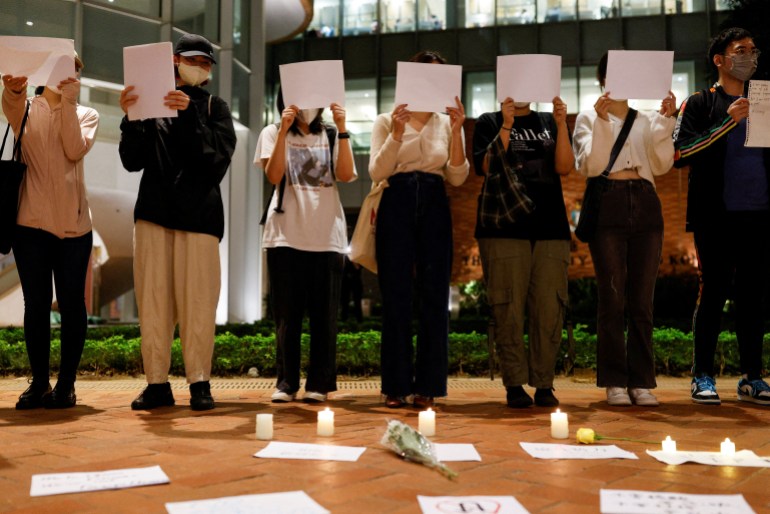

Others followed her lead, repeating the chant, and raising sheets of blank paper, a defining symbol of the latest wave of protests in China.

“I had tears in my eyes,” said Bill, a 24-year-old graduate student in Chengdu who, like all the other people interviewed for this story, asked to be identified by a pseudonym for fear of retribution. “Hearing those people chanting these words, in China of all the places, makes me feel that I have never been alone.”

“If all of us can be this brave, then this country will still have hope,” he added.

In a rare nationwide display of defiance, protests calling for an end to China’s harsh zero-COVID policy erupted over the weekend in several major cities, including Shanghai and Beijing, and on campuses of dozens of universities, creating one of the biggest political challenges to the government since the unrest in Hong Kong in 2019.

The demonstrations began after a fire in a high-rise apartment building in Xinjiang’s Urumqi last Friday that left at least 10 people dead; protesters blame the deaths on the strict measures linked to the government’s zero-COVID policies. Videos posted online showed that the barriers erected in front of the neighbourhood compound, as part of the city’s prolonged coronavirus lockdown, hampered the firefighters’ access to the building.

The outpouring of anger, at a level rarely seen in China’s tightly controlled society, consumed Chinese social media. In post after post on Weibo and WeChat, two of China’s biggest social media platforms, people demanded justice for the victims and that the government drop zero-COVID, which has slowed down the economy and upended millions of people’s lives.

“WeChat felt like a war that night,” Su, a freelance writer based in Shanghai, wrote on the platform. “Almost every minute, someone writes or reposts something that would normally be deemed too sensitive to share.”

The censors, as expected, scrambled to delete posts. Trending topics referencing the Urumqi fire, for example, were dragged down the Weibo trending list, but the sheer volume of discussion happening online took many platforms by surprise and many posts continued to circulate.

Defiance

Protests are not rare in China, but they mostly occur in limited spaces and focus on clearly defined economic problems such as labour, property and financial issue. What is unusual this time is the nationwide nature of the anger and the single, common cause of outrage.

The last nationwide political protests were in 198,9 when college students led a pro-democracy movement that swept across China. That movement ended with a bloody massacre in Tiananmen Square, putting an unspeakable yet powerful halt to nearly all subsequent grassroots protests.

“If you’ve been following Chinese politics for long enough, you have to wonder whether the anti-lockdown protests are getting near the point where serious top-down nationwide crackdown becomes pretty much inevitable,” Taisu Zhang, a professor at Yale Law School, wrote on social media.

While the Urumqi fire was the catalyst for the protesters, in some places, the demonstrations became more politically charged with zero-COVID, a key initiative of President Xi Jinping.

In Shanghai’s Wulumuqi Road, named after the city of Urumqi, protesters began to utter words that were previously unimaginable. “Communist Party,” one shouted. “Step down,” the rest of the group responded. “Xi Jinping,” another one called. “Step down,” emboldened demonstrators shouted back.

In Beijing, hundreds of people gathered on Sunday night, calling for press freedom, among other demands.

In Chengdu, crowds chanted “China doesn’t need an emperor,” an implicit reference to Xi’s third term and the removal of constitutional limits on presidential terms. In Guangzhou, crowds sang the iconic Cantonese song by the band Beyond with the line “forgive me for my life’s unbridled indulgence and love for freedom.”

One online video showed a young man standing still in front of a moving police vehicle in an apparent effort to pay tribute to the famous Tank Man of Tiananmen Square, who stood in front of a line of tanks rolling into the Square in the lead-up to the bloody crackdown in 1989.

More than 30 years later, the young man was soon shoved down and arrested by the police, along with two others who had joined him in front of the vehicle.

Anger continued despite the arrests. “If I don’t speak up due to fear of the regime, I think our people will be disappointed,” a student said during a protest at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, the alma mater of the Chinese president. “As a Tsinghua student, I’d regret this for the rest of my life.”

“We should not be afraid of our government, and even our national anthem asked us to rise up in times of hardship,” one 36-year-old veteran from the Chinese army said, referring to the Chinese national anthem that starts with the line: “Rise up, people who do not wish to be slaves.”

“I sustained many injuries as a soldier, but I do not regret it, because I’m a Chinese citizen and I believe all of us have the right as Chinese citizens to rise up,” he continued.

Policy tweaks

On the surface, the government has responded in some positive ways to the outpouring of anger: lockdowns were lifted in most places across Urumqi, while a project to build an enormous quarantine centre in Chengdu was halted overnight. Other cities have also adjusted their approaches to mass testing.

The government also announced on Tuesday it would speed up vaccination for the elderly.

But the security response has also been swift.

“The government has a playbook for dealing with these kinds of events and have been hardening the system for many years for just these kinds of threats,” longtime China-watcher Bill Bishop wrote in his Sinocism blog, noting that “political security” is “task number one” for the country’s leadership and security services.

In the initial hours of the protests, state media coverage was largely absent, with occasional mentioning of “foreign forces,” the government’s usual scapegoat.

But as the demonstrations appeared to gather steam, arrests began.

The police presence was increased in nearly all big cities, and — making use of the mass surveillance system built up over the years — the government started to identify protesters using GPS and phone services. On Tuesday, the Communist Party’s top security body called for a “crackdown” on “hostile forces”.

Many sources told Al Jazeera that they had been subjected to random phone searches, too. Online posts suggested that police were stopping people to search for apps that are banned in China, including Telegram and Twitter, and text exchanges for any mention of words like “demonstrations” or “protests”.

The question now is where this wave of protests will go.

Some of the protesters are defiant.

“We are going to keep fighting until we cannot fight anymore, and we don’t know when or how that day will come,” Su from Shanghai said.

But analysts say it is more likely that they will fizzle out, as most such movements do in nearly all countries.

“Having erupted spontaneously in a short period, they will fade away without reaching any climax or denouement,” William Hurst, a professor at the University of Cambridge and an expert on China, wrote an analysis of events on Twitter.

“A second possibility is some form of comprehensive & decisive repression. This could take the form of a coordinated and possibly quite violent crackdown (as in 1989), or it could be slower-motion and at least somewhat less bloody (as in Hong Kong in 2019-2020),” he continued.

Tough choices

Beyond the changes that have taken place so far, observers are sceptical that there will be systematic change to the zero-Covid policy, let alone any political change.

Three years since the first coronavirus cases were detected in the central city of Wuhan, lockdowns, mass testing, quarantine and tracking remain the key tools in the country’s COVID-19 response.

The government says such measures remain necessary because of a relatively low vaccination rate among the elderly, who are more vulnerable to the disease.

China has reported a record-high number of cases in the past few days, with a slight fall reported on Tuesday.

China’s vaccination campaign has been a puzzle for many.

Despite having won itself ample time to inoculate its population after the initial harsh lockdowns in early 2020, the government failed to administer sufficient vaccines to its large elderly and immunocompromised population.

There are questions too about the efficacy of Chinese-made vaccines, especially against variants such as Omicron, which are now sweeping the country.

The fear is that once the policy is relaxed, the health system will be unable to cope, and there will be a devastating surge in deaths.

But many younger people have had enough of those arguments and the seemingly endless disruption to their lives.

“It’s a matter of time before each of us gets affected by this series of stupid anti-pandemic measures,” said Max, a 23-year-old resident of Dali in southwestern Yunnan province.

“We are all fed up, so I think it’s my duty to stand up,” he added, quoting the young man filmed riding a bike into Tiananmen Square during the 1989 pro-democracy protests.